June 12, 2020

Mr. Walied Soliman, Taskforce Chair

Ontario Capital Markets Modernization Taskforce

walied.soliman@ontario.ca

C/O: Jeet Chatterjee, Senior Advisor Securities Policy

Ministry of Finance (Ontario)

jeet.chatterjee@ontario.ca

Dear Walied,

Introduction

We wish to thank you for the opportunity to present to the Ontario Capital Markets Modernization Taskforce on June 4, 2020 and the invitation of the Taskforce to provide written submissions prior to the publication of the Taskforce consultation paper.

FAIR Canada is a national, charitable organization dedicated to putting investors first. As a voice for Canadian investors, FAIR Canada is committed to advocating for strong investor protection in securities regulation.

We provide the following submissions for your consideration as a follow up to our PowerPoint presentation which is attached in Appendix A:

- Strong Regulation Leads to Strong Capital Markets

1.1 Strong protections for investors are important to attracting capital to markets and to Ontario capital market’s international competitiveness. Market integrity and investor protections are important factors to attract domestic and international investors to a market. International investors are sometimes reluctant to invest in Canadian markets relative to American markets due to a perception that investor protections and legal rights of investors are weaker in Canada. FAIR Canada submits that the Taskforce should propose strengthening regulatory protections for investors to improve Ontario’s ability to attract investment.

1.2 In our presentation to the Taskforce we provided examples of high standards and strong and effective regulation leading to strong capital markets as well as an example of how the failure to establish proper standards and inadequate regulation in Canada in the past has led to multi billion dollar losses for Canadian investors, a loss of investor confidence and inability for companies to raise capital. We would be pleased to provide more detail on the examples (based on personal experience) which are summarized below.

Hong Kong

1.3 The first example given was Hong Kong, a market that in 1989 had not recovered from the systemic weaknesses that were exposed by the 1987 stock market crash. In 1989 the Hong Kong Securities and Futures Commission (SFC) was created to overhaul every aspect of the securities and futures markets. Senior regulators from the UK, US, Australia and Canada were recruited to lead the SFC. At the same time, the inaugural issue of Asia Money featured a cover story entitled “The Slow Death of the Stock Exchange of Hong Kong”, predicting that the Hong Kong exchange would become a back water and be overtaken by Singapore, Malaysia and other smaller markets. In addition to the collapse of the stock and futures exchanges in 1987, Hong Kong was also experiencing an exodus of listed company domiciles from Hong Kong to offshore jurisdictions (in response to the impending takeover by China) effectively undermining the system for regulation of listed companies. The new SFC lead the overhaul of every aspect of the markets, including the governance of the exchanges, listed company disclosure and corporate governance, trading, clearing and settlement. The SFC addressed the redomiciling phenomenon in a flexible but effective manner. After two years without a listing post the 1987 crash and virtually no capital raising, confidence improved, and the SEHK started to recover with new listings. Capital formation resumed encouraged by new financing methods introduced by the SFC and SEHK (including introducing new private placement rules and expedited rights offerings).

1.4 With the crisis addressed, the SFC identified a strategic priority to greatly expand the market and the Hong Kong government and exchange agreed that this should be the top priority: the listing of Chinese State-Owned Enterprises (SOEs). At this stage China had a nascent legal system without a company law (let alone a securities law) and only start-up legal and accounting firms. SOEs were essentially a combined business and government providing policing, hospitals etc. where they were based. The challenge was significant.

1.5 The key players debated whether to have a lower standard for SOEs as China did not have basic laws and the management had no concept of western legal and accounting standards. The Premier of China, Zhu Rongji, quickly settled the debate in favour of the SFC position. State Owned Enterprises should be required to comply with the same enhanced standards as other Hong Kong listed companies. Premier Zhu saw Western standards of regulation (including management, governance and proper financial disclosure) as a way to improve the management and governance of SOEs. He also thought that Hong Kong listed SOEs would be perceived as “second class” companies if they were subject to lower standards. Hong Kong applied the same standards to SOEs and the SFC also required that arrangements to be put in place with China so that the SFC could effectively regulate SOEs based in China.

1.6 Within two years of the start of the initiative, the first SOEs were listed on the newly named HKEX. In the next decade Hong Kong went on to become a world leader in IPO financings, even eclipsing the NYSE some years. The prediction of the death of Hong Kong was premature. Hong Kong went on to become the top international financial centre in Asia. Hong Kong got the message and in the years to come continued to upgrade its standards to match the highest standards in the developed world.

Canada

1.7 Meanwhile in Canada, the TSX started to aggressively promote Chinese listings in the 1990s leading to over 50 new listings. However, the TSX failed to address the regulatory challenges of listing companies from China (none of which were SOEs) despite being warned of the risks. This failure extended to the investment dealers, auditors and regulators. People are familiar with the $6 billion Sino Forest fraud and the inability of the OSC to prosecute the perpetrators of the fraud. Less well-known is that through fraud and mismanagement virtually all of the other 50 or so China listings on the TSX suffered the similar fate leading to billions of dollars of additional losses for Canadian investors. The failure to establish proper regulation was a fiasco for Canadian investors and did not help the reputation of Canada.

Dubai

1.8 In 2002, Dubai launched an initiative to create the Dubai international Financial Center (DIFC) with the Dubai Financial Services Authority (DFSA) a western style regulator staffed by seasoned international regulators. The DIFC was to fill one square kilometer of desert sand with its own laws and legal and regulatory system modeled on the laws and regulations of the leading financial centers. Dubai essentially adopted the “one country, two systems” model of Hong Kong. The UAE/Dubai had local laws, but a different legal system was created within that one square kilometer. In less than 3 years, the square kilometre of sand became a square kilometre of newly built and fully occupied office towers attracting leading financial institutions from around the world. The DIFC quickly became the financial hub for the Middle East and beyond.

- Better Regulation and Regulatory Burden Reduction

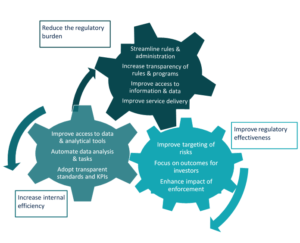

2.1 FAIR Canada supports the concept of “better regulation”, rather than simply endorsing reducing the regulatory burden. It is a recognized concept among regulators internationally that encompasses several critical objectives. Better regulation refers to ongoing efforts by a regulator to improve the way it regulates and delivers regulatory services. It includes burden reduction and improving efficiency but does not stop there – it also extends to improving regulatory effectiveness.

2.2 In our submission to the OSC on its consultation on the initiative to reduce the regulatory burden, we stated that reducing the regulatory burden is a sound goal if the core purposes of the regulatory program continue to be met effectively.

2.3 Better regulation aims to deliver better results more efficiently with fewer burdens on users. It means ensuring regulation is proportionate to the need or objective, which includes regulating less or streamlining regulation where possible, if the quality and standard of regulation is maintained. It also means regulating more or strengthening regulation when that is needed to regulate effectively.

2.4 The objectives of reducing regulatory burdens and providing sound standards of regulation that protect investors are compatible objectives, especially if burdens arise from inadequate service levels, outdated IT systems and platforms, or overly bureaucratic administrative and regulatory processes that do not improve standards of regulation. Reforms and initiatives in these kinds of areas can improve services to users, including investors as the most important beneficiaries of sound regulation.

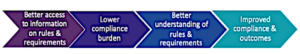

2.5 The three objectives of improving regulatory effectiveness, improving the regulator’s efficiency and reducing the regulatory burden on regulated persons and other users should be pursued collectively. Ideally, they work together in an ongoing and integrated process to produce better results, such as an improved level of compliance and a lower compliance burden on regulated persons, as shown in this graphic.

Example 1

2.6 A regulator can reduce the burden on all stakeholders by improving the clarity, accessibility and information about complex rules and requirements. At the same time, it improves users’ understanding of the rules, which should produce a higher level of compliance and better outcomes for investors.

2.7 Users have long complained about the accessibility of rules on the OSC’s website. Searches produce multiple results of rule proposals and rule changes over many years, rather than leading to one consolidated, current version of a rule. (We use the term “rule” to encompass all types of regulatory instruments that the OSC is responsible for.) This greatly increases burdens on users in terms of time spent trying to find a rule and determine what the latest version is. Few are interested in a complete history of a rule. They just want to know what is required now. This is an issue that affects all of the OSC’s stakeholders because all are users of its rulebook – the general public, regulated firms and individuals, investors, issuers of securities, professional advisors and so on.

2.8 In addition to improving access, the OSC can improve understanding of its rules by using plain language drafting principles for its rules and by publishing guidance on the way that a rule is interpreted and applied by OSC staff. The Commission has adopted plain language as a principle to be achieved in the long term (as rules are changed) and, working with the CSA, has long provided a helpful range of guidance on its rules.

Example 2

2.9 Better regulation should improve access to listed companies’ disclosure and other kinds of information made public by regulators for all of the above users, in particular investors. Improved and faster access to information and data can significantly reduce users’ costs in terms of time invested in using IT platforms to both file and search information, including websites. If information is very difficult to find and search, users may give up and fail to obtain relevant information at all, which could be even more costly. Further, advanced and flexible IT systems support better regulation by making regulatory analysis and processes faster and more effective.

2.10 FAIR Canada’s submission to the OSC on its initiative to reduce the regulatory burden is available here.

- Ontario should withdraw from the Cooperative Capital Markets Regulatory Authority / National Securities Portal Proposal

3.1 The Taskforce should recommend that Ontario abandon its support for the Cooperative Capital Markets Regulatory System initiative. The initiative is not worth pursuing further due to several major deficiencies including the absence of several key provinces, the lengthy and resource intensive cost of the initiative that no longer has a real political champion, and the loss of Ontario’s influence on national policy and control of Ontario’s capital markets. Ontario is the key capital market in Canada and, in the OSC, has the most important capital markets regulatory agency.

3.2 We believe the Ministry of Finance (Ontario) and the OSC should refocus their resources on delivering changes and programs to improve regulation of our capital markets, improve services to investors and other market participants and attract new investment to Ontario.

3.3 The allure of a single national regulator, including as a tool for burden reduction, is understandable. It is also misguided. There are reasons why reform proposals for a national regulator have gone unfulfilled for over 50 years and will continue to go unfulfilled, all the while consuming massive resources, stirring up conflict and going nowhere.

3.4 FAIR Canada has a better suggestion: a “National Securities Portal”, instead of a “National Securities Regulator” that would address and resolve the conflict over a national regulator while addressing the burden imposed by fragmented, outdated, complicated and inconsistent systems to deliver and access important information and disclosure.

3.5 A national securities portal and database is a practical alternative to a national securities regulator. This proposal will result in major reduction in regulatory burden and resolve decades of federal-provincial conflict and waste.

Current systems are a burden

3.6 Capital markets industry, shareholders and investors bear the burden of plethora of provincial and other jurisdictional systems and interfaces. The few nationwide systems that exist – SEDAR, NRD and SEDI for disclosure, industry participant filings and insider trading filings, respectively – are outdated, unfriendly, unsearchable and slow.

3.7 NRD is very difficult to search and analyze data. There is no simple way for investors to search the disciplinary history or information on an investment advisor because the information is spread around several data bases and not consolidated.

3.8 Similarly, SEDAR is far from a user-friendly source of disclosures from publicly-traded companies and is also very difficult to search. Why is a code needed for investors to search a public database of corporate disclosures? Simply put, SEDAR is not fit for its purpose. There is a CSA initiative in existence with CGI to replace the SEDAR system. However, it was begun in 2016 and there isn’t clear visibility as to where it currently stands, its breadth and whether it addresses any of the newer industry issues additional to the old ones.

3.9 How difficult must access to information be for retail investors if it is so complicated for securities industry professionals and experts? Even the regulators call to action by investors to check the registration status and disciplinary history of any financial advisor is easier said than done. The information is scattered around different databases and also is incomplete.

3.10 One of the main purposes of these systems is to provide public access to disclosure about issuers, registrants and insiders. Regulators place a high degree of reliance and emphasis on full disclosure and transparency by issuers and in the markets. As such, the current state of these systems is unacceptable.

3.11 In addition, more flexible systems that employ document formats that can easily be searched, filtered and analyzed using the latest analytics tools would be far more useful to staff at the OSC and other CSA members in their regulatory activities, which would lead to more effective and efficient regulation.

3.12 FAIR Canada believes that the state of these national systems and other IT systems provided by regulators in Canada underlines the imperative to create a National Securities Portal. The current approach to developing and maintaining national systems, and regulators’ IT systems generally, is not working effectively.

A National Securities Portal Solution

3.13 FAIR Canada proposes that the Canadian provincial and federal governments and regulators prioritize the creation of a “National Securities Portal” as an alternative to a “National Securities Regulator”.

3.14 The proposed Capital Markets Regulatory Authority (CMRA) is not national. At best it is partial and hybrid, excluding systemically important jurisdictions. Problems with a fragmented system will not be solved when provinces like Quebec and Alberta will never participate. This is a slow moving, expensive quagmire that has consumed a decade attempting to reconcile irreconcilable legal and political conflict.

3.15 On the other hand, provinces opposed to the national regulator would probably agree to a National Securities Portal, especially if proposed in exchange for dropping the national regulator project. Provinces would save significant costs. A single modern system would exist for disclosure filings, regulatory correspondence and fees, for example. It would be more usable and searchable with standardized search protocols to greatly improve speed. Access to information would be a practical reality, not a theoretical one.

3.16 A National Securities Portal could also be designed to centralize reporting on financial fraud to consolidate into a single system documentation on financial fraud reporting that is otherwise separated amongst a wide array of police and regulatory databases. A financial fraud database could include, for example, reporting to the Ontario Provincial Police, Royal Canadian Mounted Police, securities regulators, anti-money laundering regulators and banking regulators in Canada.

3.17 A data-driven, information technology system would also enable data analytics and artificial intelligence applications, improving on capital markets risk management, proactive risk and systemic risk early identification and investor protection.

An information technology project would also create an opportunity to design prospectively, not only to manage past needs but new and novel ones that represent not only where the capital markets have been but where finance and fintech are going.

3.18 To create this new information technology system for the capital markets industry and to address the emerging fintech industry, governments and regulators should create a separate private company to build and administer a national IT system with its own governance structure and dedicated resources to ensure timely and centralized decision-making. Revenue would be shared among the provinces based on provincial fees. The new entity would be responsible for maintenance and adherence to the highest security and risk standards. FAIR Canada urges that new system development be holistic, forward looking, separated, funded and prioritized.

3.19 FAIR Canada believes that developing a National Securities Portal is a solution that isn’t just good in theory but that is also viable and deliverable. It would significantly reduce regulatory burden, improve access to information, enable data driven intelligence and serve the public interest, all at a lower cost.

- Strengthening the SRO system of regulation

4.1 SROs in Canada play a significant and expansive role in Canadian securities regulation, so FAIR Canada believes it is important for the Taskforce to consider the SROs’ role and effectiveness in its recommendations on modernizing securities regulation and enhancing the attractiveness of capital markets in Canada and Ontario. SROs provide the frontline regulation of the business conduct and financial and operational obligations of investment firms, providing investment advice to clients, and trading in equities markets and derivatives markets.

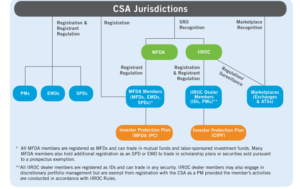

4.2 Canada’s securities regulatory structure is complex, with 13 statutory regulators and several SROs, including IIROC, the MFDA and the Montreal Exchange (MX or Bourse de Montréal). These three SROs are responsible for regulating investment firms, salespersons and investment advisors. IIROC also regulates trading on many securities markets for equities, as well as the debt markets. The Bourse also regulates its derivatives market. In addition, several exchanges – most notably the TSX and TSX Venture markets – play an important role in regulating their listed issuers and approve new listings of securities.[1] Finally, recognized clearing and depository agencies[2] owned by the TMX Group provide vital market infrastructure that plays a critical role in the Canadian financial system. All of these organizations are licensed or “recognized” by CSA members and subject to ongoing CSA oversight.

4.3 The roles of IIROC and MFDA are illustrated in this graphic, which does not include the role of the Bourse or the listings functions of securities exchanges. It also shows how all of the provincial regulators, IIROC and the MFDA are responsible for registration, regulation and supervision functions of various types of investment firms.

Source: MFDA, A Proposal for a Modern SRO (2020)

4.4 This complex regulatory structure is fragmented, somewhat opaque and poorly understood by the public, and often within the securities industry itself. Firms of various types and their personnel are subject to different but largely similar rules, registration requirements, forms of supervision and compliance obligations. Most of the duplications could be addressed by a merger of IIROC and the MFDA, the SROs that regulate dealings with investor clients. The CSA’s review appears to be mainly driven by the latest industry proposal to merge IIROC and the MFDA.

4.5 A merger could produce several benefits, including simplifying the regulatory system, eliminating duplication in rules and supervision, and improving the system’s ability to deliver regulatory services more consistently and efficiently across the industry. Potentially, a new SRO could regulate not only current IIROC and MFDA member firms, but also other firms that provide investment services to consumers but are now directly regulated by provincial regulators in a patchwork system.

4.6 Such a proposal would create a larger, more powerful SRO with broader jurisdiction that would play a major role in regulating the securities industry and securities markets. The long term significance of such a development for capital markets must be carefully considered and planned. That would constitute a structural change in the national regulatory system, not just a basic change at an operational level.

4.7 FAIR Canada believes the SRO system needs to be strengthened in several key areas before such an expansion of the SROs’ role and authority can be justified. In its submission to the CSA on the proposed review of the framework of the SRO system, FAIR Canada advocated that the regulators undertake a comprehensive and broad-based assessment of the current system and how it can be strengthened. If the CSA considers a merger proposal, it should ensure that the SRO framework and the new SRO responds to the public interest in ensuring sound and independent regulation of capital markets.

4.8 It would be completely inadequate to merely merge the two SROs’ existing operations under the current self-regulatory model given the shortcomings of the current SRO system. We recognize that benefits could be achieved and many could theoretically help investors, especially a simpler system and rules applicable to all dealings with investors. But the SRO system must demonstrate that it will more effectively serve and protect investors before governments and the CSA can justify greater reliance on a new merged SRO.

4.9 Our position is that the CSA must consider whether self-regulation is working effectively in the public interest and in providing investor protections. We believe that SROs’ current practices in areas like corporate governance, transparency and enforcement raise important concerns. Specifics of our concerns are set out in our submission to the CSA here.

4.10 These concerns raise questions about the SROs’ level of commitment to protecting investors and ensuring their rights are respected by investment firms. If the regulatory system is to rely on SROs to an even greater degree, current practices in those areas must be improved. Furthermore, the CSA must ensure that detailed plans are developed to ensure proper oversight of the new SRO’s governance and operations, and accountability for results.

4.11 FAIR Canada proposed that the CSA review should cover:

- The rationale for using SROs to regulate capital markets and whether self-regulation is working in the public interest

- The scope of SRO regulation

- The SROs’ corporate governance systems

- The SROs’ mandates and responsiveness to the public interest

- The effectiveness of SROs in regulating markets and registrants, and protecting investors from abuses and unfair practices

- The CSA’s oversight of the SRO

4.12 Importantly, in almost all other markets around the world other than the US, reliance on self-regulation has been declining for several decades now. There are many factors for this trend, including the advent of for-profit securities exchanges which historically performed SRO roles, strengthening of statutory regulators in many countries and heightened concerns about the conflicts of interest that are inherent in self-regulation. If Canada chooses a different path, it must be clearly justified by identifying real benefits to investors and all stakeholders in the capital markets, not just to the securities industry.

4.13 FAIR Canada’s submission to the CSA on its review of the SRO system is available here.

- Awarding Compensation to Investors Harmed by Misconduct

5.1 Access to justice for retail investors in Ontario is inadequate. Victims of financial misconduct in many cases suffer devastating losses and impacts on their lives. In many cases for retail investors, the impact of these losses results in diminished retirement savings and the inability to finance the cost of their children’s post-secondary education. The impact of this harm to financial, emotional, psychological and physical health is a deterrent to many potential investors from participating in investments in securities due to loss of confidence in the integrity and fairness of the capital markets and the ability of regulatory bodies to provide meaningful investor protection.

5.2 FAIR Canada recommends that the OSC be provided with a clear mandate and ability to order financial compensation to aggrieved investors. The Expert Panel on Securities Regulation in Canada Final Report, January 2009[1] to the Minister of Finance (Canada) included this recommendation. The OSC has the ability to apply to a court for a compensation order in favour of victims of financial loss due to breach of the Securities Act but it does not have the power to order restitution directly to investors. The OSC must have this power and a clear mandate to seek compensation for victims of violations of the Securities Act.

5.3 Too often where the regulator undertakes an investigation with an investment scam, this may be of little benefit to the victims as the regulator’s focus is on bringing enforcement proceedings, securing findings against the persons charged with offences and imposing administrative sanctions such as removing trading privileges or imposing fines. The victims of the violation who often brought the matter to the attention of the regulators are left to their own devices when it comes to seeking compensation.

5.4 Public outcry about the lack of or inadequate punishment for violators of securities laws is further aggravated by the fact that, in many cases, victims of misconduct by dealers and financial advisors recover very little of their losses, if anything at all. In Canada, there are limited options available to investors to recover losses sustained as a result of securities law violations.

5.5 In their research and recommendations to the 2006 Task Force to Modernize Securities Legislation in Canada, by Peter Cory and Marilyn Pilkington, a survey of the plethora of reform proposals and research studies in Canada concluded that essential improvements to the enforcement of securities laws included (1) express authority for securities regulators to apply to a court for compensation for victims of financial losses, (2) greater use of existing powers of this type, (3) new powers for securities tribunals to order restitution and (4) jurisdiction of courts to order restitution.

5.6 The OSC 2019 annual report discloses that through its enforcement proceedings $10.9 million was ordered or agreed to be returned to investors. Contrast this with the U.S., where the system seems simpler and the tools are more powerful. Since 2002, the U.S. Securities & Exchange Commission has been using a mechanism called Fair Fund, created as a result of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002, to return US$14.5 billion to investors – an average of US$1.3 billion per year.

5.7 FAIR Canada believes that an increased focus on victim compensation would further the OSC’s mandate to protect investors and foster confidence in the integrity and fairness of capital markets in Ontario. The use of this power would reduce the need for wronged investors to seek access to overburdened and expensive civil courts in order to enforce their rights.

5.8 Traditionally the IIROC and the MFDA’s’ enforcement actions in Ontario have not considered potential compensation of investors harmed by misconduct. They impose penalties intended to punish improper conduct and deter similar conduct, but financial penalties do not encompass disgorgement of profits from misconduct to clients who suffered damages as a result of the conduct, or compensation of such clients for financial harm due to the misconduct. Investors must rely on the lengthy and difficult client complaints process of the dealer (including a so called “ombudsman”), a flawed ombudsman process for review of claims, or costly litigation (which is simply not accessible to most retail investors) to pursue compensation for losses caused by misconduct. Notices from SROs of disciplinary actions, decisions and settlements with dealers and individual registrants rarely state whether the financial firms have compensated investors who suffered harm or been required to disgorge profits.

5.9 By comparison, the securities industry SRO in the U.S., the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA) specifically provides for disgorgement of ill-gotten gains and compensation or restitution to investors[2]. FINRA mandates that its adjudicative tribunals and staff prioritize the compensation of investors for harm caused by its member firms through its sanction guidelines[3] and its policy on credit for cooperation in enforcement matters[4]. The contrast between the US SRO experience and the lack of such focus in Canada has been the subject of recent media scrutiny in Ontario[5]. FINRA reports that its highest priority when addressing misconduct is returning money to harmed investors. This stands in stark contrast to the priorities of either IIROC or the MFDA.

5.10 Investors that invest through IIROC or MFDA member registrants are able to seek non-binding dispute resolution through OBSI for claims of compensation up to a maximum of $350,000 and, for IIROC member registrants, binding arbitration resolution through IIROC arbitration proceedings for claims up to a maximum of $500,000. Fees for arbitration services are shared between the IIROC member and the client.

5.11 Independent expert reports have long recommended that in order to make the process more efficient and effective for investors and to comply with international standards, OBSI should be empowered to make binding compensation orders. This position has recently been acknowledged as a goal of the Chair of the OSC[6].

5.12 Under the current non-binding OBSI regime, if a registrant firm rejects a compensation recommendation from OBSI, the consequence is to be publicly “named and shamed” by OBSI. However, some registrant firms employ a practice of making an offer to settle with the investor that is a fraction of the OBSI recommended amount (a “lowball offer”), accompanied by a threat to not pay any compensation if the investor rejects the offer. If the investor accepts the “lowball offer”, the registrant firm requires the investor to enter into a non-disclosure agreement that precludes the investor from disclosing the misconduct or the terms of the settlement.

5.13 The total compensation awarded by OBSI for both banking and investments related complaints in Canada in 2019 was only $2.67 million. The average award for investments complaints was only $14,291. Even if binding power resulted in a 100% increase in compensation it would be totally insignificant to the financial industry.

5.14 Some argue that it does not really matter because the vast majority of OBSI cases are resolved with registrant firms following the recommendation for compensation by OBSI. However, the issue isn’t that simple. Recalcitrant registrant firms are able to ignore OBSI with relative impunity. This undermines investor confidence in the integrity and fairness of Ontario’s capital markets and has a negative impact on their decisions whether or not to invest.

5.15 Moreover, the “name and shame” power of OBSI has not been effective at bringing recalcitrant firms to heel. This is a systemic problem that tilts the playing field in a way that places consumers at an unfair disadvantage. This gap in the enforceability of OBSI awards, undermines public confidence in the securities industry and damages the reputations of all investment firms. FAIR Canada has written about this issue several times.[7]

- All Investments Regulated by OSC/Preventing Improper Regulatory Arbitrage

Regulation of Segregated Funds

6.1 The Ontario Securities Commission should regulate segregated funds in light of the following:

- the expertise of the Ontario Securities Commission in regulating complex investment products;

- the basic principle that consumers should receive a similar level of protection in respect of their investments and advice related to those investments regardless of which sector of the financial industry the product or sale originates from;

- the basic principle that like products should be regulated in like manner so that consumers have good outcomes: and

- the separate regulatory silos make no sense when a client has both mutual funds and segregated funds in an account, the client is required to file two separate complaints with two different ombudsman services (one for investments and the other for insurance), how does this make sense?

6.2 If for political reasons this is not possible, then harmonization of the regulatory framework is needed so that regulatory requirements are the same: the advice provided by life insurers, managing general agencies and life insurance agencies and their life insurance agents on the insurance side should be at the same standard as that required of dealers, advisers and their registered representatives on the securities side; relationship disclosure requirements, cost and performance disclosure requirements for insurance products with an investment component and point of sale requirements should all be similar. This is especially true since the access point for the sale of these products is often the same individual who is dually licensed.

- Additional Points:

Electronic Access to Disclosure Documents

7.1 FAIR Canada supports eliminating delivery of paper documents if the new rules ensure that investors receive specific notification of delivery of a document and how the document can be viewed. We support the OSC’s initiative to publish a proposal on this subject as part of its regulatory burden reduction project.[8]

7.2 We agree that replacing delivery of paper documents with fully electronic access to disclosure documents, client statements and other documents would greatly improve efficiency, reduce costs and improve investors’ access to documents. Most investors and clients of investment firms prefer instant access to documents on their computers to mail. Documents in soft copy can be downloaded for analysis and storage, if desired.

7.3 The new rules on delivery must require the document to be attached to an email sent to the investor or the notice must include an online link to the document. Sending a link to a website that must then be searched to find the document in question is not adequate. The link should produce the specific document to be delivered. (Of course sign-in must be required to access non-public documents such as client account statements and in those cases a link to the sign-in page should suffice.)

7.4 FAIR Canada does not support adoption of a simple “access equals delivery” model, if it means that as long as a person has access to a document online then he/she is deemed to have received delivery. An email notification that “a document is available” is not proper notice of delivery of a document. The type of document must be stated. The basic ability to access a document online is not helpful unless notice is received that a specific document is being delivered. Furthermore, it must be included with the notice or directly accessible from it. The regulators need to recognize that online access is not the same as delivery unless those additional requirements apply.

7.5 The option of receiving a hard copy on request for people who have no or limited internet access or seniors who have difficulty with online documents should be retained.

7.6 FAIR Canada’s submission to the OSC on electronic delivery of documents is available here.

Corporate disclosure improvements

Streamline disclosure filings for issuers

7.7 FAIR Canada supports streamlining of disclosure filings and documents and reducing duplicative disclosure requirements because that would both improve the usability of disclosure documents for investors and other users of disclosures, as well as reduce burdens on issuers. We support the OSC’s proposals on this subject as part of its regulatory burden reduction project. They include:

- Changes to annual information form (AIF) and management discussion and analysis (MD&A) requirements to avoid duplication[9]

- Changes to rules on investment funds to consolidate the simplified prospectus and annual information forms, streamline material change reports and address duplicative requirements[10]

7.8 Consolidating the content of periodic disclosures into one document or form makes sense. It would reduce the burdens and costs involved in meeting duplicative requirements for issuers. It would be easier for investors and others to access and obtain information about companies by reducing the number of documents to be reviewed and eliminating overlapping content in them.

Improvements in quality of disclosure

7.9 We also suggest that the Taskforce endorse continued efforts by the OSC to improve the quality of disclosure by issuers. Improvements in disclosure have been made over the last decade or so thanks to the OSC’s selective review program of corporate disclosures. This program identifies a selection of issuers for a comprehensive review of their full disclosure record over a period of time. The program is primarily remedial in nature, resulting in guidance to issuers on how to improve the quality of disclosure. In some cases issuers are required to restate or refile their disclosures to address shortcomings. The OSC should be commended for these efforts to improve disclosure practices.

7.10 More improvements are still needed to ensure disclosure is clear, understandable and specific to the issuer’s business and circumstances. Use of generic, boilerplate statements should be discouraged or prohibited, particularly in commentary on a company’s business operations and the risks that it faces. For example, analyses of risks and broader trends in an industry or market should address the specific impact or potential impact on the company in question, rather than simply setting out general points that could apply to companies in its industry or even more widely.

7.11 The OSC has made the point on the need for specificity in disclosures regularly and we suggest that the Taskforce encourage the OSC to increase efforts to ensure relevant disclosure is made; for instance by requiring more issuers to revise disclosures that lack the degree of specificity and detail necessary to understand the impact or potential impact of the point in question.

Summary documents for public and private offers

7.12 We propose that investment dealers be permitted to provide summary disclosure or offer documents that highlight key points of new issues to client investors. Summary documents are already permitted to be used to sell products like mutual funds and ETFs (“Fund Facts”) and structured notes. Summaries typically known as “green sheets” are prepared by investment dealers for internal use and would be useful to investors but are not allowed to be given to retail investors.

7.13 Limiting documents available to clients for corporate issues to the full prospectus is more confusing than helpful as key points are lost. Very few people will read a long prospectus. If an investor has an investment advisor, the advisor will outline the key points of an issue verbally based on the “green sheet”. In many cases it would be preferable to simply send out the document, which clients would find useful. Investors using discount brokers do not have access to verbal advice so would clearly benefit from making a summary document available.

Adopt service standards for responses to participants

7.14 In its November 2019 report on its regulatory burden reduction initiatives, the OSC promised to adopt and publish service standards that cover more processes, and to establish a framework for performance measurement and continues improvement.[11] FAIR Canada fully endorses those proposals. They should improve efficiency in delivering regulatory services. If the standards are transparent as proposed, they will help to manage expectations of regulated persons and users of OSC services.

7.15 It is important that the OSC consistently meet the service standards, provided that it does not make compromises in the quality of regulation to do so. To that end, their promise to use them in performance measures is welcome. We suggest that the results of performance assessments on service standards also be published to ensure accountability and to inform the public and regulated persons on whether the standards are usually met.

Enforcement

7.16 Enforcement is a vital part of securities regulation and a critical component of investor protection. As we state in this submission, strong regulation leads to strong capital markets and clearly active enforcement programs are an important part of strong regulation. But many concerns remain with the effectiveness of enforcement mechanisms and fraud prevention in Canada including:

- Failure to successfully prosecute frauds

- Effectiveness of enforcement in identifying and dealing with violations

- Do penalties reflect the harm done and are they real deterrents to misconduct?

7.17 Although the Taskforce is primarily concerned with the OSC given its mandate, enforcement in the capital markets arena involves many players. That includes entities that are responsible for investigating violations and prosecuting or disciplining transgressors. The system is very fragmented in Canada, although that is also true of the US, whose record of enforcement of capital markets laws, rules and regulations has been widely lauded for many years.

7.18 In Canada the main players are:

- The OSC and all the other provincial regulators that comprise the CSA

- The RCMP, mainly through its Integrated Market Enforcement Team (IMET)

- Local police forces that deal with frauds

- The criminal justice system; in Ontario through the Crown prosecutor’s office

- The SROs, primarily IIROC and the MFDA.

7.19 The fragmented nature of enforcement makes taking action and introducing reforms difficult. In part this fragmentation reflects the wide range of bodies responsible for regulating capital markets with authority to make laws, rules and regulations. That includes the federal and provincial governments, the provincial regulators and the SROs. It also makes taking a consistent approach to enforcement across Canada challenging. Only the SROs and RCMP IMET are national in nature and even they have regional differences in their approaches. Changes are generally made by one authority at a time and given that the provinces are primarily responsible for securities regulation a national approach to making reforms has rarely been taken.

7.20 Enforcement issues in the capital markets arena have been reviewed before and has been the subject of detailed comment in advisory committees’ reports before too. For example, the IDA Task Force to Modernize Securities Legislation in Canada, whose report was issued in 2006, made a long list of recommendations pertaining to enforcement. Very few were ever acted upon.

7.21 FAIR Canada has long urged reforms to enforcement programs in capital markets. We have been especially critical of the system’s ability to deal with criminal frauds. We suggest to the Taskforce that it is again time for the administration of enforcement in capital markets to be reviewed by an expert panel. The system is simply too complex and complicated for the Taskforce to address in the limited timeframe it has to make recommendations. Also, the specialized nature of investigation and enforcement programs means that a review should be carried out by an expert panel comprised of people who are familiar with the enforcement system in Ontario and Canada, the legal and regulatory processes involved and the shortcomings in enforcement programs.

7.22 The mandate of a panel charged with reviewing enforcement should be to recommend changes to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of enforcement in Ontario (or Canada if the mandate is national). That should include examining enforcement programs at the SROs, which are an important part of the overall enforcement system for capital markets, especially in firms’ dealings with clients and supervising trading activity in the markets. FAIR Canada has specific concerns about the focus, strength and transparency of the SROs’ enforcement programs, as noted in section 4 of this submission.

7.23 Examples of the large number of reforms that might be considered in a thorough review of enforcement in this arena include:

- Creating a national program for the relevant authorities to improve cooperation on enforcement issues, priorities and tools

- Developing a centralized database to support enforcement programs, with sophisticated data collection, reporting and analysis tools

- Creating an independent, national capital markets court

We would be pleased to discuss these submissions with the members of the Taskforce should they have any questions. Please feel free to contact Ermanno Pascutto, Executive Director FAIR Canada at ermanno.pascutto@faircanada.ca or Douglas Walker, Deputy Director FAIR Canada at douglas.walker@faircanada.ca

Yours sincerely,

Ermanno Pascutto

Executive Director – FAIR Canada

About FAIR Canada

FAIR Canada is a national, independent charitable organization dedicated to being a catalyst for the advancement of the rights of investors and financial consumers in Canada. As the voice of the Canadian investor and financial consumer, FAIR Canada advances its mission through outreach and education, public policy submissions to government and regulators, proactive identification of emerging issues and other initiatives. FAIR has a reputation for independence, thought leadership in public policy and moving the needle in the interests of retail investors and financial consumers.

[1] Other recognized exchange that perform listings functions include the Canadian Securities Exchange (CSE) and the NEO Exchange

[2] Canadian Depository for Securities Limited (CDS) and the Canadian Derivatives Clearing Corporation (CDCC). CDS is a wholly-owned subsidiary of TMX Group. CDCC is a wholly-owned subsidiary of the Montreal Exchange which in turn is part of the TMX Group.

[3] http://www.expertpanel.ca/eng/documents/Expert_Panel_Final_Report_And_Recommendations.pdf> at page 35

[4]https://www.finra.org/investors/have-problem/legitimate-avenues-recovery-investment-losses

[5]https://www.finra.org/rules-guidance/oversight-enforcement/sanction-guidelines

[6]https://www.finra.org/rules-guidance/notices/19-23

[9]https://faircanada.ca/whats-new/who-benefits-and-who-loses-from-keeping-obsi-toothless/ and https://faircanada.ca/whats-new/independent-review-of-obsis-mandate-concludes-binding-decision-making-power-is-needed/ and https://www.investmentexecutive.com/insight/letters-to-the-editor/time-to-pull-the-plug-on-obsi/

[10] Decisions C-11 and F-10, OSC update report on Reducing the Regulatory Burden in Ontario’s Capital Markets, November 2019

[11] Decision C-10, OSC update report on Reducing the Regulatory Burden in Ontario’s Capital Markets, November 2019

[12] Decisions F-4, F-7 and F-9

[13] Decision A-3 and A-14